The Guardian

October 2015 An island paradise: white beaches and palm trees, glittering water, bare-chested fishermen, children eating breadfruit. The scenes painted by Clement Siatous at first appear to be anodyne pictures of a tropical fantasy, the sort you might find in the market of a cruise-ship port of call. They are nothing of the sort. They are historical documents – fraught, fragmentary and intensely sad.

Siatous, the subject of a vital and melancholy exhibition at Simon Preston Gallery in New York, is now a citizen of Mauritius. But he was born on the Chagos Islands, a British territory in the Indian Ocean – and the site of one of the most sordid episodes of Cold War gamesmanship. When the United States needed a military base in the region, the UK scythed the Chagos Islands from colonial Mauritius and named it the British Indian Ocean Territory, which was falsely claimed to be uninhabited. (In the jargon of the CIA, the native population was designated as NEGL: negligible.) The US established a huge naval base on the island of Diego Garcia, the UK got millions of dollars in clandestine payments, and the Chagossians, Siatous among them, were expelled from their homes and sent thousands of miles away.

The Chagossians have spent decades fighting to return – assisted by a once-obscure backbench MP named Jeremy Corbyn – but the archipelago’s strategic importance to the US and UK weighs against them. It has been widely alleged that the base at Diego Garcia has been used for the CIA’s extraordinary rendition program: the extrajudicial practice of kidnapping, interrogation, and at times torture. More recently, the UK government attempted to designate the islands as a nature reserve, which, according to a 2010 US state department cable provided by Chelsea Manning to Wikileaks, was intended to scupper Chaggosian claims to resettlement. (“The environmental lobby is far more powerful than the Chagossians’ advocates,” a UK diplomat reportedly said.) This past March, a UN tribunal ruled that the marine designation was illegal.

Siatous was born in 1947 on the atoll of Peros Banhos – pictured here as a place of thatched huts and subsistence fishing, with a well-attended church complete with stained- glass windows. As a child he and his family moved to the larger island of Diego Garcia, but when, in 1968, he traveled to Mauritius for medical treatment, the British authorities refused to let him return. Only then did he start painting. He is self-taught; his use of colour is extraordinary, though his figures can be schematic at times. But aesthetics matter less than narratives in the 18 paintings on display here, each one an evocation of a past erased.

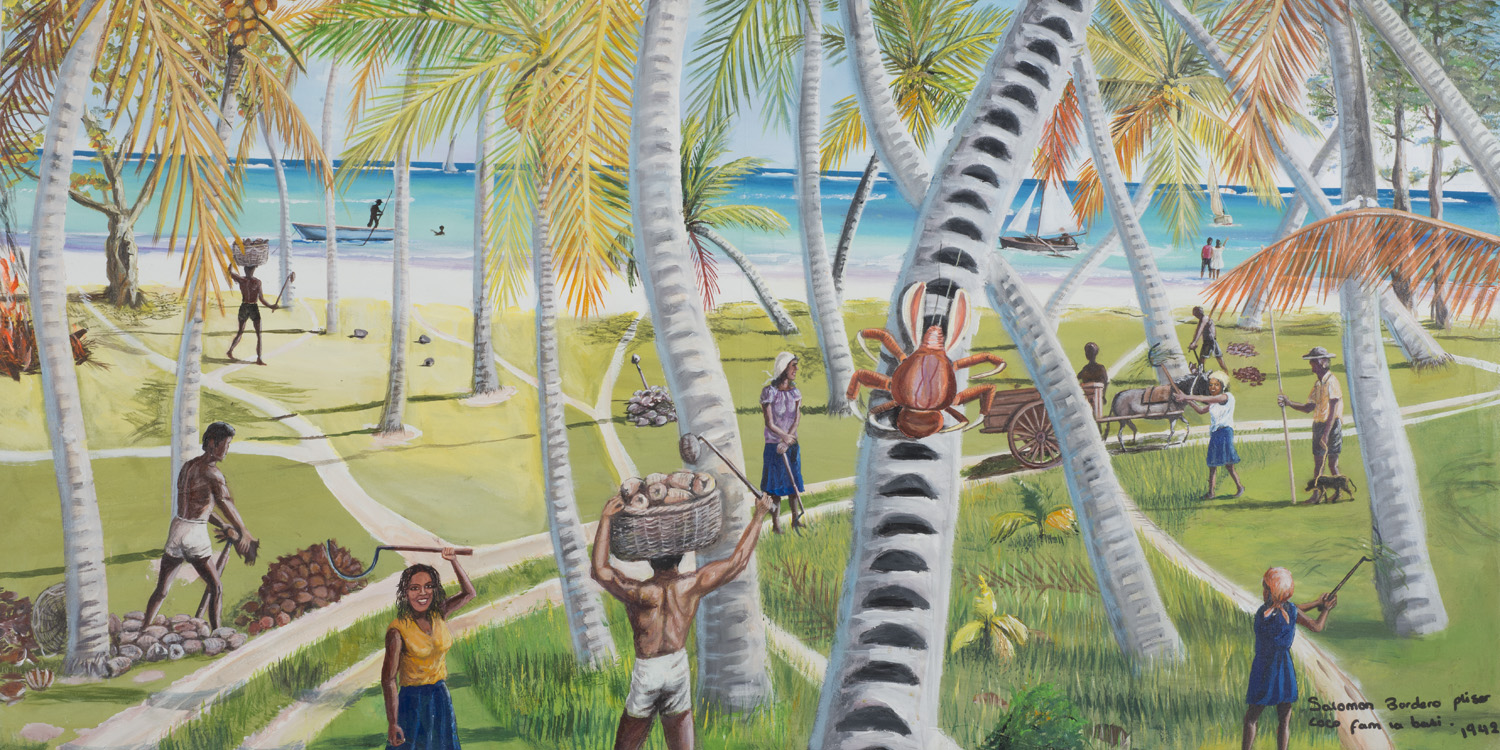

In Siatous’s tableaux of life on the Chagos Islands, we see seaplanes and commercial vessels alongside horse mills and old-style rowboats. A woman hauls coconuts in a wicker basket perched on her head; bales of guano are hoisted onto ships. Tradition and modernity intermingle easily in these scenes of Chagossian life, and the wide grins on his figures’ faces foreshadow a grim future. On the sparsely populated Chagos Islands, resources were plentiful. In Mauritius, the Seychelles, and the UK, Chagossians have faced unemployment and abject poverty.

These paintings were completed between 2001 and 2015, but each one has been designated with a specific year it evokes, before the final exile of the Chagossians in 1973. For they are not fantasias. They are careful, exacting incarnations of individual memories and passages in the artist’s life and the life of his community. After all, the British lie that the Chagos islands were uninhabited was possible in part because the native population had little written or photographic evidence of their 200 years of residence. Each one of Siatous’s paintings is thus a means to discredit that falsehood, an ex post facto document of a society denied its right to a home. One plantation scene, featuring men harvesting coconuts and a grinning woman wielding a scythe, is dated to 1942 – before Siatous was born. The memories these paintings represent are therefore communal memories, embodiments of a history the US and UK insist never took place.

This downhearted, poignant show has been organized by Paula Naughton, who has spent years documenting the history of the Chagos Islands, and it’s entitled Sagren: a word in the now obsolescent Chagossian creole, derived from the French chagrin, o regret. Sagren, to the Chagos refugees, signifies a mix of nostalgia, desperation and overwhelming sorrow – a sickness for home so intense it can be lethal. Next year, the United States’ 50-year lease on Diego Garcia expires. A judgment on resettlement is pending in the UK supreme court. Siatous may yet go home, to paint the Chagos Islands not from memory but from sight.

Jason Farago

www.theguardian.com

www.jasonfarago.com

Art Review

December 2015

In 1973 the British Government forcibly expelled the indigenous inhabitants of the Chagos Islands, a strategically located Indian Ocean archipelago, to facilitate the establishment of a US naval installation on the atoll of Diego Garcia. Crucial to the US’s Cold War strategy of containment, the island has more recently served as a base for bombing and reconnaissance flights over Iraq and Afghanistan. Concurrent with the removal, the British authorities initiated a programme of historical erasure, claiming that the Chagos Islands had never hosted a permanent population, an obfuscation made easier by the scant visual record of this remote territory.

The history of the archipelago is a nexus of conflicting narratives and disproportionate political power: the Pax Americana, the War on Terror and the Chagossians’ memories of their home and their desire to return. The islanders’ longing is summarized by the Creole world ‘sagren’, and it is embedded in the work of Clement Siatous, who was born on Diego Garcia in 1947 and has lived in Mauritius since 1973.

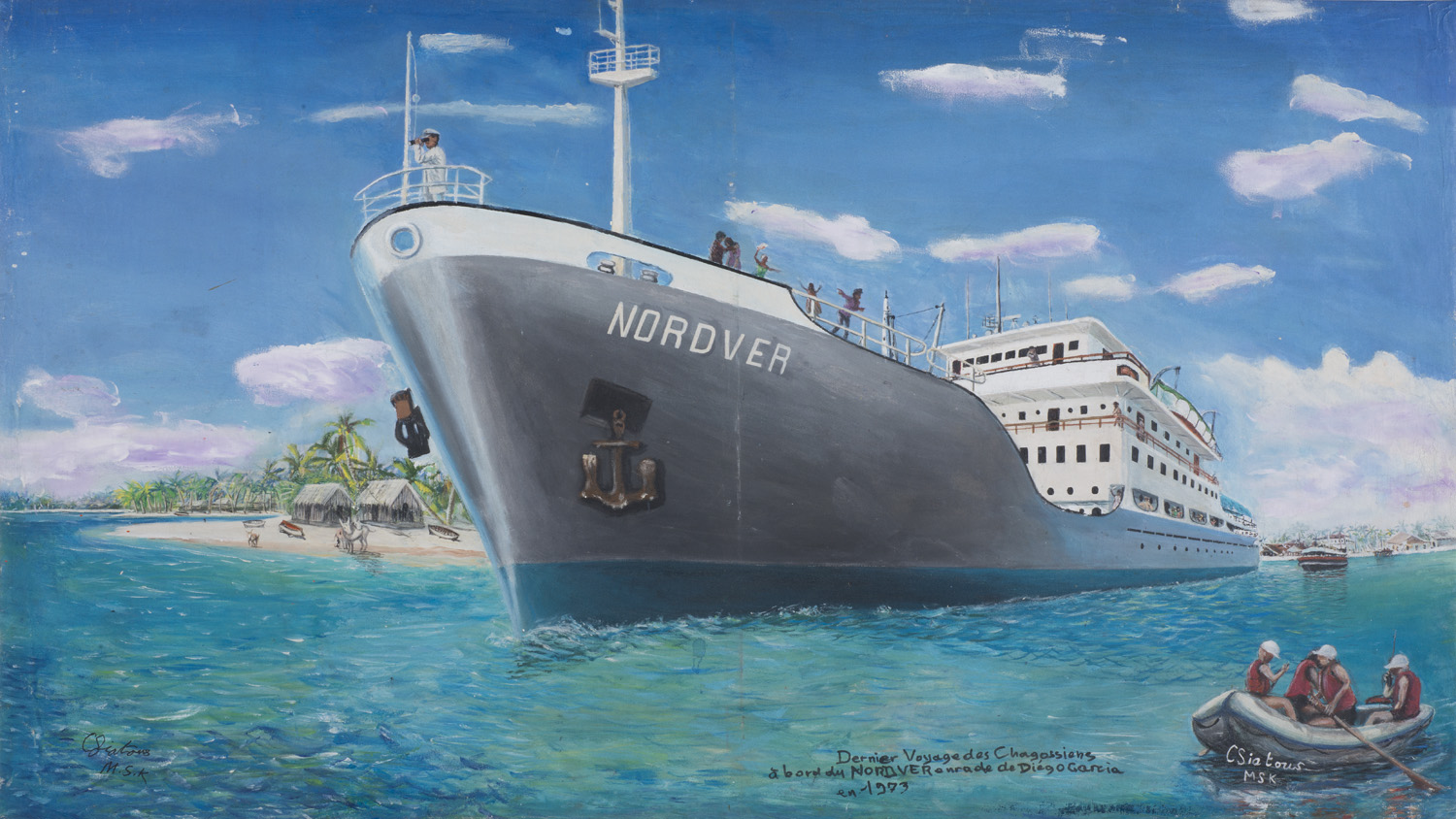

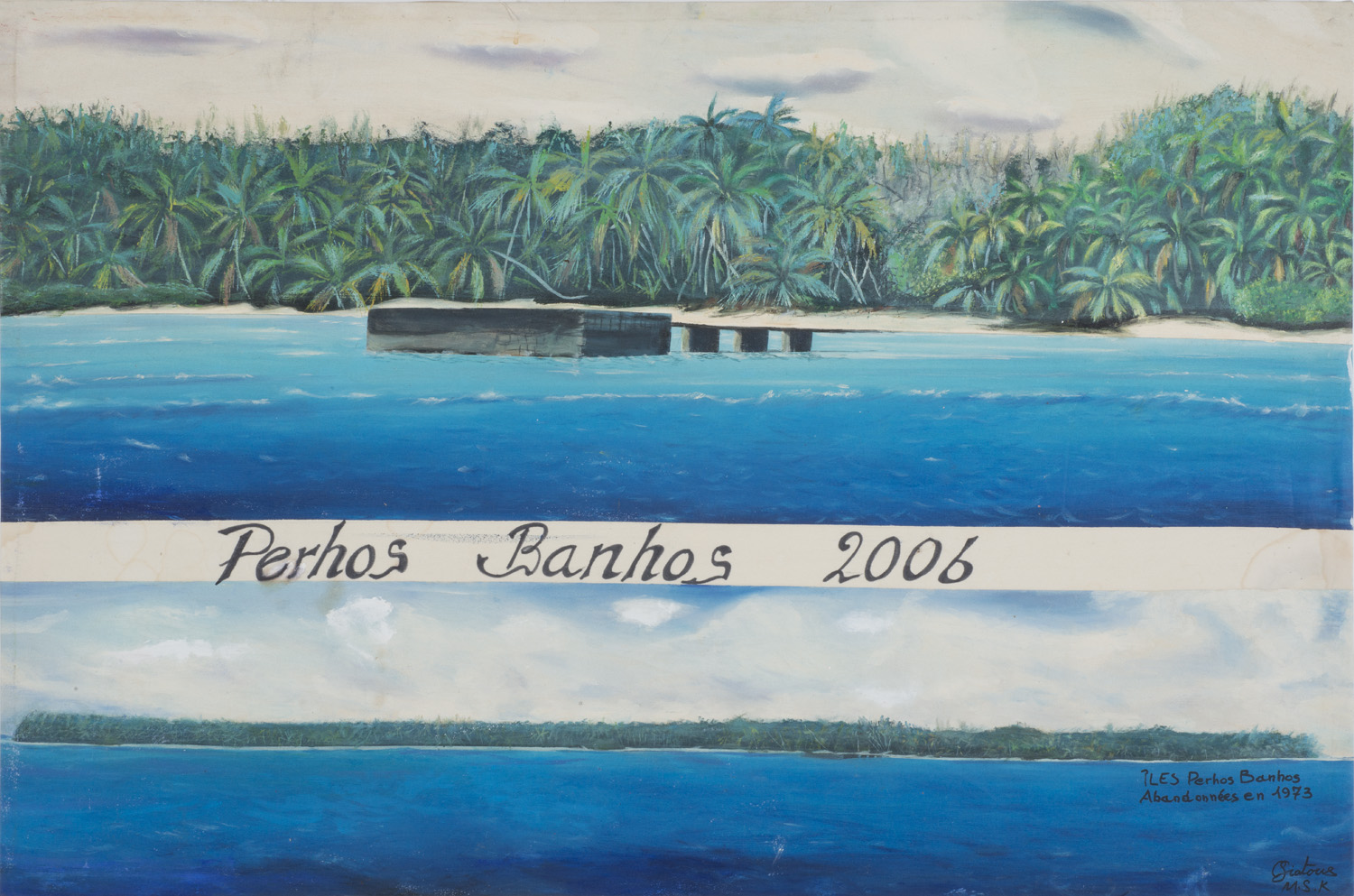

His paintings (those shown here were created over the past 15 years) depict an idyllic life based on copra production, fishing and small-scale guano mining. In one, a massive crab scales a palm tree. In another, a robust woman carries a basket of massive coconuts. Such images of contented plenty contrast with others, such as one of Chagossians sailing into exile, or a representation of the overgrown island of Perhos Banhos, with its rotting jetty the last evidence of its former inhabitants.

Siatous inscribes each work with a descriptive notation and a date, as if it were an ethnographic view or documentary photo. Together the paintings form a history cycle of rootedness and removal. The bright, acrylic palette, its infelicities of scale and perspective, which recall the few extant nineteenth-century watercolors of the area, and the inclusion of small details, such as a pair of donkeys, one resting its head on the back of the other, that watch as the last inhabitants sail away from Diego Garcia—all this heightens the cycle’s poignancy.

Like Native American or Palestinian artists who incorporate traditional motifs or references to popular culture, Siatous is reclaiming heritage to resist its willful obliteration. The show itself constitutes part of the New Atlantis Project, maintained by Paula Naughton (who also directs Simon Preston Gallery), which documents Chagossian history and advocates for repatriation and reparations. Yet the force of Siatous’s work derives not from tis political intent but from its emotional sincerity. It is as much about the life the Chagossians lost as their memories of it, and thus of the ties to tradition and to place that bind a people to a land and cannot be explained wholly by theory, documentary or ‘fact’, but by spirit alone.

Joshua Mack

www.artreview.com

Artnet

At Simon Preston, Clement Siatous's Self-taught Conceptualism

THE DAILY PIC (#1392): This painting is by Clement Siatous, born on the Chagos Islands in 1947, and it's part of an important solo show that recently opened at Simon Preston Gallery in New York, where it was curated by Paula Naughton. Although Siatous is self-taught, it's important to realize that he's not another one of those “outsider" artists that the art world is in love with right now.

Despite a superficial look of naïve outsiderism, his work in fact fits in with the political and documentary trends of the last 30 years of contemporary art. His paintings of labor and boats on his home islands need to be considered alongside the knowing labor and fishing photos of Allan Sekula, not the wild imaginings of Henry Darger.

As I understand it, Siatous's paintings are reflections of the life he left behind on Chagos when he and every one of his neighbors were exiled from that Indian Ocean archipelago in the 1960s and early ‘70s. Despite much (living, breathing) evidence to the contrary, the British overlords had declared the islands uninhabited, so as to hand them over to the U.S. for use as a military base. They proceeded to make their declaration come true.

Living in exile between Mauritius and Britain, Siatous uses his paintings as unimpeachable documents of the life he and his people were forced to leave behind, and of the true inhabitation of the home taken from them.

Siatous follows a process that any conceptualist would be proud of: He chooses a very particular place and instant in the pre-exile past of Chagos, and then does his very

best – I'm told a very accurte best – to recreate the scene, as he remembers and can document it. His paintings are political and informational objects rather than traditional esthetic ones. (Although for me they also have a hint of John Baldessari's procedural art.)

That means that they shouldn't be appreciated according to the criteria usually applied to outsider art – as “directly expressive", as “innocently joyful," as “escaping from deadening conventions". (As I've argued before, those are terms used by Western modernism – still alive and well in some quarters today – to appropriate and assimilate the art of outsiders. Their works are treated as aesthetic objets trouvés that ignore their original meanings and functions.)

The particular style and look of Siatous's pictures should be seen as irrelevant; they could have been painted utterly differently, either better or worse. What matters is that they were painted just well enough to give simple, transparent access to the information they carry and bear witness to. They function as true-enough documents of injustices done, no more nor less than that.

That makes them important, and cutting-edge.

Blake Gopnik

www.news.artnet.com

Frieze

Issue 175 November - December 2015 The paintings in Clement Siatous’s exhibition ‘Sagren’ are seemingly touristic depictions of daily life in a tropical seaside village. Their backstory interrupts that idyllic image, however. Siatous hails from the Chagos Islands in the middle of the Indian Ocean, where he – along with all the others who lived there – were forcibly evicted by the British government in the 1970s. The archipelago was then leased to the US for a military base involved in extraordinary rendition. Scant photographic evidence of pre-eviction life helped to support the claim of the Western powers that nobody lived there. ‘Sagren’ argues otherwise.

At a time when indigenous-rights groups maintain Instagram accounts and Facebook pages – Chagossian refugees have used crowdfunding to support their cause via the lighthearted Chagos Island Football team project – Siatous’s decision to paint is striking. It is partially about creating a counter-memory, using one of the oldest technologies in the world, painting, to reassert the presence and identity of a culture distrustful of newer imaging technologies with their guise of objectivity. But it is also about an activist sense of time; the sum of the marks that went into their own slow creation. Patience is a radical gesture. More than four decades have passed since the Chagossians were deported and, if anything, the pressure to return has increased.

Siatous paints a matriarchy. He renders the women with facial details and personality not readily found in his depictions of men. Things were better, the artist seems to imply, when women ruled.

Porteuse de Coco pour plantation 1950 (Coconut Bearer for the Plantation 1950, 2003) is dominated by the portrait of a muscled woman with a open, toothy smile who balances a basket of coconuts on her head. Her floral dress could double as breastplate armour. She towers over the landscape. This was the show’s only close-up portrait, and her scale suggests that she’s more of a goddess of strength and abundance than a villager – a goddess with her bra strap showing. It’s an eye-catching detail for Siatous to include – and not a sexualized one – which humanizes the female colossus.

Her counterpart is a white captain in a white uniform and cap. He appears in two paintings, surveying the island then piloting the eviction ship away (Diego Garcia Katalina sur zil, 2015; Dernier Voyage des Chagossiens a bord du Nordvar anrade Diego Garcia, en 1973, 2006). Each time he’s hunched over on deck, hiding his face with binoculars. For this intruder, distance power and cowardice have fused into a single thing.

Diego (2015), the exhibition’s centrepiece, hung on a wall painted orange. A pair of coconut-touting women dressed in blue with their backs to us converse in the centre of the painting. The island scene appears to emanate outwards from them, as if what they remember is what we must see: self-sufficient people working amid abundant flora and fauna. On the right, a girl scratches her head as she unselfconsciously peers at the viewer; on the left, sits a dog. The gazes of the two figures who look directly at us suggest honesty, a way to say: ‘What I’m showing you is true.’

These paintings are documents. Outside of them, denial of Chagossian subjecthood is total. The basics of the situation can be grasped by quoting the entirety of a 1971 memo sent to UK officials by the US Chief of Naval Operations, regarding the archipelago’s thousands of inhabitants: ‘Absolutely must go.’ What happens at the level of that sentence mushrooms upward into shadowy statecraft, and it is precisely these clipped, official silencings that Siatous’s images defy. In a better world, Siatous’s paintings would claim their right to be kitsch. Until the Chagossians establish a right to return, they are much more than that.

Jace Clayton

www.frieze.com

www.jaceclayton.com

The New York Times

The Best in Art of 2015

By HOLLAND COTTER and ROBERTA SMITH Dec. 9, 2015

The co-chief art critics for The New York Times on the most notable themes of the year.

www.thenewyorktimes.com

9. Solo Shows

Living artists of all ages shone in solo gallery shows: Richard Serra’s not-quite cubes of solid steel formed a spiritual union with surrounding space at David Zwirner.Cecily Brown presented the best paintings of her career at Maccarone. Karma attended splendidly to Stanley Whitney’s paintings and drawings. Dona Nelson continued to attack painting front and back with vehement color at Thomas Erben. Jamie Isentein’s performing sculptures returned at Andrew Kreps. In his debut at Simon Preston Gallery, Clement Siatous turned the painterly political in 13 sunlit beach scenes that revisited life on an island in the Indian Ocean before the United States Navy took over. And in an outstanding sophomore appearance, on view until Dec. 20, Lucy Dodd cultivates her unusual fusion of Color Field painting, sewing, cooking, music and hanging out in a mutating show at David Lewis.